|

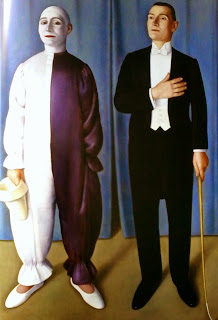

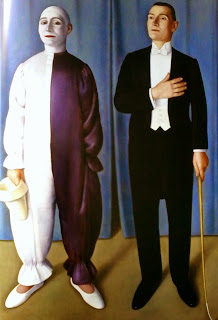

| Antonio DONGHI, Cirque équestre,1927 |

At the Bonnard exhibition last week, I saw this poster and knew nothing about the exhibition at all. The poster was enticing don’t you think?

I glanced through the catalogue when we were in the shop and decided that I would come back to see it. This would be the first time that I would see an Exhibition of Italian art which panned over 40 years.

|

| Vittorio Zecchin, Les Mille et Une Nuits, around 1914 |

In Italy in the early twentieth century the decorative arts were used to interpret the desire for progress of a nation that had only just found its unity. Cabinetmakers, ceramicists and glass-makers all worked together with the leading artists, creating a veritable "Italian style ».

|

| Bénitier, Fontaine sainte, 1921 |

|

| Domenica Baccaini, Vase Envol de femmes,1909-1910 |

|

| Adolfo Wildt, Auoportrait, 1909 |

|

| Chaise pour le salon escargot , 1902 |

|

| Elephant, 1934-35 |

|

| Umberto Bellotto, Bottle, 1922 |

This period of extraordinary creativity is recalled through around a hundred works in a chronological display. The "Liberty" style, which came into its own at the turn of the century, with designs by Carlo Bugatti, Eugenio Quarti and Federico Tesio mixed with works by the Divisionist painters. A second section is devoted to Futurism, its esthetic inspired by progress and speed extending to every aspect of life. This has always been the period I preferred so I knew this would be interesting.

Later, the return to classicism in Italy came in various guises, finding its expression in the ceramics of Gio Ponti or the glass creations of Carlo Scarpa, up to the stern language of the « Novecento". By now, Italy was under the fascist regime.

The question that came to mind when I was strolling through the exhibition, was how can exceptional creativity exist in a country heading for disaster? Did a “dolce vita” come into being before the expression was immortalised by Frederico Fellini in the 1960s?

Italy is a country which creates original styles, often inspired by different regional traditions. This I hadn’t really taken into account before today.

Venice, thanks to its geographical position and one of my favourite Italian cities has always been a crossroads of cultures. Since 1895 it is the seat of the Biennale, the leading venue for international exhibitions. There have been a couple of chapters to tell our story.

The avant-garde movement founded by the poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in 1909, was Futurism which opposed the “traditionalism” of bourgeois, academic and museum culture. It expressed the desire for renewal based on the exaltation of progress and speed.

Many of these artists I knew and many I didn’t. No photos were permitted so it was either trying to find everything on Internet or buying the « L’Objet d’Art » a small catalogue on the exhibition. I opted for the second choice.

The the artists I knew were Giacomo Balla, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo and Gino Severini. In February 1910 they signed the Manifesto of Futurist Painters and the following April, the Technical Manifesto. It must have been very avant-garde for the period.

|

| Gino Severin, Rythme plastique du 14 juillet, 1913 |

|

| Gino Severini, Danseuse Articulée, 1915 |

|

| Umberto Boccioni, Visions simultanées, 1912 |

|

| Tapestry, 1920 |

|

| gino-severini-la-danse-de-la-mer |

|

| luigi-russolo-dynamisme-d-une-automobile |

Dynamism was the essence of the new painting:

In 1917, Giorgio de Chirico, of Greek origin who had always been far from the avant-garde world, met Filippo de Pisis and Carlo Carrà at the military hospital in Ferrara. Out of this encounter was born, in the midst of World War I, the Metafisica For a short time, Giorgio Morandi was also involved in the movement. He is an artist I admire immensely because of his minimalist approach.

|

| Giorgio De Chirico, Les Archelogues, 1927 |

|

| Giorgio Morandi, Métaphysique 1918 |

|

| De Chiricio Autoportrait au buste d'Euripide 1922-23 |

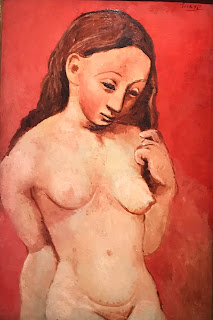

1922 saw the birth of the Novecento Italiano movement, supported by influential art critic Margherita Sarfatti. Among the first to join were Sironi, Funi and Oppi, who, looking back into the past, gave rise to a “modern classicism” founded on purity of forms and harmony of composition. So more artists I knew nothing about. And when looking at their work which was interesting in the context but perhaps not « me » for future exhibitions.

Aligning with the artistic Novecento, which would become the “official” expression of the fascist regime, the production of furniture took on robust and simplified forms.

|

| Emilio Malerba, Masques 1922 | | |

|

| Ubaldo Oppi, Friends, 1924 |

|

| Chevalier à plumes -Fortunato Depero, 1923 |

|

| Felice Casorati, Portrait of Renato Gualino 1923-24 |

|

| Ubadlo Oppi, his wife, 1922 |

|

| Felice Casorati, Silvana Cenni, 1922 |

In 1926, a group of young architects in Lombardy, including Giuseppe Terragni, influenced by the theories of Gropius and Le Corbusier, for whom the shapes of buildings were very important and they founded “Gruppo 7”, giving birth to the Italian rationalist movement. Soon architects from all over Italy became members. There is an exhibition of Corbusier on in Paris at the moment, but it’s not on my list. I find him hard to take but this is probably because of his political background.

Among the most significant examples of this transition period are innovative objects such as Franco Albini’s Radio and Gio Ponti’s Bilia Lamp, designed in 1931, judged far too avant-garde at the time, and only put into production many years later.

|

| Gio Ponti, Lampe Bilia 1931 |

So we have now crossed the 40 years. Well there isn’t too much detail but I needed to put something down on paper so I could hopefully recall what I had seen and which period it belonged which. That might be a lot more difficult.

Commentaires